#13. Ordeal by mobilization

- Elena Koneva

- Oct 13, 2022

- 17 min read

Post-release #13, October 8, 2022

Elena Koneva

This release is based on the data from two waves of the Chronicles Project express survey conducted jointly with ExtremeScan on September 21-22 and September 29-30, 2022. The method and sample information can be found at the end of the text. The analysis uses combined data from the two waves.

First Reaction to the Mobilization Decision

During the first two days after the mobilization announcement, when the first wave of the express survey was conducted, 38% already knew about the mobilization announcement and 56% had heard something about it. The first recorded reaction to the declaration of partial mobilization showed: 51% supported the decision.

The wording of the question:

On September 21, Vladimir Putin announced the decision to initiate a partial mobilization of the Russian population to participate in the military operation. Do you support or not support such a decision made by Vladimir Putin, find it difficult to answer unequivocally, or do you not want to answer this question?

On September 21-22, 2022, 51% of Russian residents were in support of the mobilization decision. Within a week (by September 29-30) this figure rose to 54%. The combined figure for the two waves totaled 52%.

The following analysis is performed based on the combined data of the two waves.

In our opinion, these are very high figures, since we are talking not simply about confidence in the president or support for an operation somewhere abroad. Half of the Russian population agreed with the necessity of measures that involve risks to their health and lives and their inevitable participation in lethal actions in a neighboring state.

The fact that it was Putin who personally gave the order to mobilize – just as he had previously announced the recognition of the LPR and DPR, then the special military operation, not leaving the TV screens for 7 months – played a large role. It is very likely that what we have measured so far is specifically the support for Putin's decision, rather than a conscious attitude toward expanding the military contingent using irregular troops that are not volunteers or even prisoners but are forcibly called up from the reserve.

The 52% of support for the mobilization, as well as for the special operation as a whole, is a projection of real trust to the authorities, but such figures clearly do not reach the level of 75-80% of rallying 'round the flag that state pollsters claim.

It was originally assumed that support for mobilization would be a relatively independent parameter since we are no longer talking about Kremlin's symbols or some vague distant operation abroad, but rather about actions that directly affect the respondents or their loved ones. But on all the questions that measure loyalty in one way or another, we see the same indicators.

It has also become one of the main indicators of the military campaign being unsuccessful. According to the Levada Center, "in September the percentage of those who believe that the 'special military operation' is proceeding successfully decreased. While in May there were 73% of such people, in September they amounted to 53%. About a third (31%) believe that the 'special operation' is not going on successfully. Speaking of the unsuccessful course of the 'special operation', respondents explain it by saying that everything "has been dragging on, for six months now, no end in sight" (27%), there is "mobilization, people started getting drafted" (23%), "we are losing, giving up land, not advancing, retreating" (22%)."

Demographic and Class Stratification in Relation to the Mobilization

As the express survey has shown, the attitude toward mobilization is another form of support for the special operation.

The demographic characteristics of the groups segmented by attitude toward the mobilization are similar to those we observed in our analysis of attitudes toward the military operation.

Young people (18-34 years old) are half as likely as older people (55+) to support the mobilization: 34% vs. 70%.

Young women constitute a distinct group: they have the lowest indicators of support and the highest indicators of direct non-support.

Financial status affects both support for the special military operation and attitudes toward the mobilization: less wealthy respondents are significantly less likely to support the current developments than those with wealth: 45% vs. 65%.

Occupation is also a significant parameter of influence: housewives (including young women on maternity leave) – 33%, law-enforcement officers, siloviki – 72%.

Mobilization: the Daughter of the Special Operation

For respondents, mobilization is perceived as a continuation of the 'special operation', although in the first case the war will soon materialize as hundreds of thousands or even millions of families affected, while in the second case it was about an operation taking place far beyond Russian borders, with stated 'good' goals: 'denazification', 'demilitarization', 'protection of the population of Donbas', etc.

Analyzing the factors influencing the support for the special military operation, we saw that due to the distorted information flow and specific features of the Russian mindset, one cannot count on the empathy of the majority of the Russian population towards Ukrainians.

Another group of factors is related to the negative personal consequences of the special operation.

Mobilization is the most significant and most massive event in the period of the hostilities, with potentially dire consequences for Russian citizens. It was assumed that it would become clear to people: the mobilization will affect everyone, will spare neither the opponents nor the supporters of the 'special operation', and will have, as one of its elements, an impact on the general loyalty syndrome. But so far, in the early days, few people have fully realized what has happened, and how they should react to it.

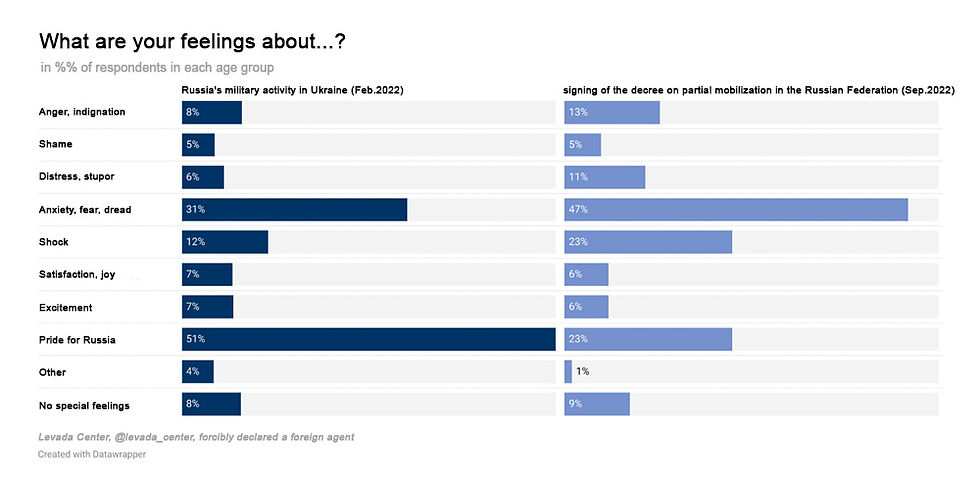

The mobilization inherited a level of nominal support for the special operation, but the vast majority of people experienced a whole range of negative emotions: anxiety, fear, and horror (47%), shock (23%), and stupor (11%).

The high involvement in this event shows its unprecedented character, even compared to the launch of the 'special operation' in February 2022.

It will take time and people's first-hand experience before we see the results of the "mobilization operation" becoming increasingly tangible for Russian residents, which will have an effect on the overall perception of the war. The dynamics of the support for the special military operation are already distinctly negative: from May to mid-July it fell from 64% to 55%, and in the express survey it showed 52%.

Subjects to Mobilization: Paradoxical Effect on Support

The data show that a significant share of the population accepts mobilization as an inevitable given. Another hypothesis about the negative impact of the fact or threat of the draft proved to be unfounded.

The question in the interview sounded as follows:

Do you think that under Vladimir Putin's decision to mobilize, will you personally or someone in your family be subject to mobilization or not? (Check all the boxes that apply). Operator: If the respondent says that they or a family member has already been mobilized, check boxes 5 or 6.

1. Yes, the respondent will. 2. Yes, someone in the family will. 3. No one will. 4. The respondent does not know. 5. The respondent is already mobilized. 6. Some relatives have already been mobilized.

The number of search engine queries about recruitment criteria was off the charts for the first few days. Thousands of potential recruits headed for the borders. Respondents answered according to their understanding of the mobilization criteria. The final figures reflected the result of a clash of opposing scenarios. Some citizens turn a blind eye to real events and believe that they have a deferment or discharge. Others are afraid of being mobilized, regardless of their eligibility for the draft, and there are more and more of them as word gets out about "excessive measures", when everyone gets drafted.

According to the survey, 11% of respondents are personally subject to mobilization, and 29% of respondents have relatives who are subject to mobilization.

Unexpectedly, the support for mobilization turned out to be higher among those who are subject to the draft. If respondents themselves qualify for mobilization, they are more likely to support it – 66% compared to 52% for the population as a whole.

We recorded a similar pattern with respect to the willingness to participate personally in hostilities. For the population as a whole we got 35%. If a respondent believes that they are subject to mobilization, they are almost twice as likely to realize this potential: 63% of potential recruits are willing to go to war. If any of their relatives can be drafted, the willingness-to-fight figures also rise.

Throughout the past months of the war we have been trying to answer the question of why this unnatural and, from the point of view of an outside observer, inhumane 'special operation' is being supported.

The main reasons are obvious: lack of understanding of what is happening, escape from reality, internalization of the propaganda framework, and apoliticality and hopelessness consciously molded by the state. But there are other motives as well. Based on indirect indicators, we have been able to identify a core group of genuine conscious support for the mobilization.

In the current context, we have built our model on direct verifiable attributes: support for the mobilization, willingness to participate in it, and unwillingness to interrupt the war.

The "hawks" segment is 19%. These are those who:

supported the mobilization,

expressed willingness to participate in hostilities,

are not willing to accept Putin's potential decision to interrupt the military operation without achieving its objectives.

Compared to the overall structure of the population, this group includes more men, especially those of older age, more people with higher financial status, and, not surprisingly, people working for security agencies.

When asked about the reasons for their support, they talk about civic duty - "because there is a war going on" - mentioning the images of the enemy and of the imperative to defend the homeland formed by propaganda, repeating key propaganda talking points about the need to destroy the fascists.

For every hawk in the pro-war party there are 2-3 moderate supporters of the mobilization – those who, while supporting it, are still not willing to participate personally in hostilities and, in general, are not against a decision to end the war. "Loyalists" are willing to go along with the authorities' decisions if it does not require personal sacrifice.

If we take those who support the mobilization, while not being a "hawk", then their open responses reveal other motives: "so that the war can end," support for the authorities, and "you can't get away, this is the way it has to be". In other words, this is a whole other level of support, much less militant and more associated with general loyalty to the authorities, not excluding an interruption of the 'operation' and a transition to peace negotiations.

The reasons for supporting the mobilization correlate directly with the goals of the special operation. In the respondents' answers we see signs of a paradigm shift from an offensive to a defensive one. This is both a reflection of the official rhetoric and the result of the protraction of the war, as well as such significant factors as the announced mobilization.

Previously, rhetoric related to actions on the territory of Ukraine dominated in respondents' open answers: protection of the Russian-speaking population of the LPR/DPR, denazification, demilitarization, overthrow of the Ukrainian government, capture/return of Russian territory, and saving Ukrainians. Now actions of a defensive nature are named: defense (this is the dominant word in answers to open questions) of the homeland, defending Russia from Ukraine (less frequently), from NATO, from the West, "to stop the war", to end it quickly, to support the army.

The motive of war with the West and NATO works especially well for the mobilization, because "the forces are not equal" and it is necessary to balance them.

To some extent, verbal support for mobilization is an unconscious reflection of the new phase of the war, the phase of failure (according to the Levada Center, mobilization is the second marker of an unsuccessful operation after its apparent protraction).

There is diverse mythology associated with this: that people are facing a choice between mobilization and "the enemy at the gate", that new recruits will not be thrown into the offensive, but will be placed in a defensive perimeter on Russian territory, that mobilization is needed as a temporary measure to let servicemen go on leave, and other such versions, which are voiced in discussions on social networks.

Other factors influencing readiness to fight have been well studied during the war months. We have written an entire "encyclopedia" about them, and all of its findings are fully confirmed today.

For example, in June we wrote about the influence of the socio-economic depression factor on readiness for a mobilization:

“The declaration of willingness to participate in the special operation is not so much a basis for predicting a volunteer movement as a reflection of general loyalty to the authorities, Putin, and the operation itself, shaped by long-standing and currently pertinent propaganda.

A real willingness to go to war can only in a small part be the result of ideological beliefs. Its scale should be predicted on the basis of personal socio-economic circumstances, the degree of being marginalized, job loss, loss of loved ones in the war.”

The Other Russia

We are looking for ways to properly count and analyze those who do not agree with the justifiability of the mobilization, do not support the military operation, are not willing to go to war, and other disloyal citizens.

This has been the question researchers have been facing since the beginning of the "special operation," and the problem of getting answers from people in a situation of censorship and under the threat of persecution has not abated.

As a result of experimenting with the wording of sensitive questions, we have developed an approach that provides a more accurate picture of the size and characteristics of the group of those who in general do not support the mobilization, the special operation, who are not willing to go to war, who are willing to interrupt the special operation, etc.

With a high degree of accuracy and for the purpose of analysis, we can combine the directly "disloyal" respondents (those who say "I do not support") with those who found it difficult to answer or refused to answer. In support of this, we present a comparative table based on the data from the Express survey.

The correlations with other questions show that the respondents who indicated their disapproval of the mobilization and the military operation itself are people who largely coincide in their views with those who refused to answer the question and those who found it difficult to answer.

A reminder: the tables reflect the values of significance. The numbers in light blue are those that are significantly smaller, and the numbers in pink are those that are significantly larger. We compare the groups of respondents who explicitly do not support the military action and the combined group, which in addition included those who found it difficult to answer and those who refused to answer this question.

Mobilization Support Segmentation

In quantitative projects, researchers produce numbers that they give names to: "nationwide support", "total trust", "willingness to participate". Even if the data is obtained correctly and without manipulation, these entities without analysis begin to play an unjustifiably large role. For example, such stigmas are cited as confirmation for various kinds of elections and referendums.

It is necessary to analyze hard numbers and build segments with consistent characteristics.

Let us model simple groups at the intersection of different bases.

Mobilization supporters

Hawks (already mentioned above):

Support the mobilization

Are willing to participate in hostilities

Are not willing to support an interruption of the operation

Loyalists

Support the mobilization

Are willing to support an interruption of the operation (if Putin decides so)

Active supporters of the mobilization

Support the mobilization

Are willing to participate in hostilities

Passive supporters of the mobilization

Support the mobilization

Mobilization opponents

Radical pacifists

Do not support the mobilization

Are not willing to participate in hostilities

Are willing to support an interruption of the operation

Pacifists (a broader group)

Do not support the mobilization

Are not willing to participate in hostilities

Are willing to support an interruption of the operation

+ Those who found it difficult or refused to answer these three questions.

The table shows how these segments overlap and differ on fundamental grounds: gender, age, and wealth.

In particular, the core stratum that rejects the mobilization as well as the war in general, as we have seen in our war-related measurements, is young women.

This is an amazing phenomenon.

In the first days after the military operation was announced, young women opposed the special operation more than other groups, believed less than others that Ukraine was a threat, and did not expect a friendly welcome from Ukrainians.

If we can call a demographic group a pocket of resistance, it is them – young women. Meanwhile, they are the least represented in any government decision-making bodies.

Extreme Media Behavior

The influence of television on the perception of events as opposed to the Internet is obvious, and we simply present a table of media consumption at the intersection of the two most polar segments: hawks and radical pacifists.

Thanks to the fact that the study was conducted in two waves, we had the opportunity to see how media consumption changes in unique situations, when it is vital not only to learn the news, but also to constantly monitor the changing situation.

Media consumption as a whole rose sharply during the week.

The informational input of television increased: from 63% to 72%. Apparently, television, as a background source, is turned on and is on all the time.

Interaction with relatives and friends increased from 25% to 36%.

But the most significant growth we saw was in news from the Internet, social networks and messengers – 15%.

Changes in the media behavior of respondents across various age and mobilization attitude groups these days show an increased importance of friends and relatives for those aged 40-59. And among young people the use of social networks and messengers doubled.

And another notable observation. Those who support the mobilization increased the percentage of discussing the mobilization with their loved ones: from 19% to 33%. Opponents of the mobilization hardly increased their communication with relatives and friends. This is not surprising: among them (opponents of the special operation) there are 43% of those who had stopped communicating with their relatives over their disagreements (against 23% among supporters), i.e. the circle of communication is stable and there is no particular capacity for expanding it.

Can We Understand Russians?

Nominally, at the level of a rational response, 52% of respondents supported the mobilization decision, and a certain proportion of these people are motivated by duty, defending Russia from an external enemy, supporting the army, and the hope that this will help end the war. Some are ready to comply without much thought: to sign call-up papers, pack their bags, and report to the military commissariat (registration and enlistment office).

But what do people feel when they do this? How similar are these emotions to what they experienced at the beginning of the 'special operation'?

The Levada Center provides a vivid comparison of the two events. For half of Russia's residents the event at the end of February was radically different in their perception, a matter of pride and enthusiasm. Now, seven months later, when the war has come for your loved ones and yourself, even with the declared consent, the palette of feelings has become radically inverted: anxiety, horror, and shock dominate Russian society.

The coming weeks and months of war will convert this condition into a more conscious, informed dissent, first to the "partial" mobilization, and then to the war itself.

According to surveys, almost no one believes in either the mobilization being partial or the special operation.

Methodology of the Express Survey and Specific Features of Surveys in Russia during the Hostilities in Ukraine

Fact sheet prepared by Vladimir Zvonovsky.

The survey was conducted through the efforts of several call centers on 21-22.09.22 and 29-30.09.22 by random sampling of telephone numbers (RDD). Ranges of numbers distributed by Rossvyaz across telephone operators were used as the frame of the population. Only cell phone numbers (DEF codes) were used.

1,000 adult residents of the Russian Federation were interviewed in the first wave, and 800 in the second. The sample was stratified by Federal District, Moscow and Moscow Oblast, and St. Petersburg and Leningrad Oblast (10 strata in total).

The total number of interviewers who participated in the survey was 169. The average duration of the interview was 6 min. 47 sec. The number of contact attempts per number in the starting sample was 3. Estimated sampling error 3.09% at 95% confidence interval.

Today's standard telephone survey procedure begins with a randomly generated sample of telephone numbers being loaded into the dialing system, then a special program, which may be called a dialing robot, or dialer, dials the number. After the number is dialed, the robot receives dial responses from the telephone exchanges and networks the numbers of which it has dialed. These responses are most often generated by other robots. For example, the "busy" or "the subscriber is out of range" signals can be programmed differently by different operators. One as a "no answer" signal ("the subscriber is currently on the line"), the other one as a "busy" signal. In either case, the dialing robot interacts with other robots (R-R interaction) and interprets the stations' responses.

Only after the receiver on the other end of the line is picked up, and the dialing robot assumes it is picked up by a human, is the connection forwarded to an interviewer.

The interviewer begins the interaction with the respondent. This is the S-I (subscriber-interviewer) interaction. In this regard, it makes sense to consider quantitative parameters of this interaction only. The R-R interaction runs entirely in automatic mode, and within it determining the statuses of the respondent's readiness and ability to participate in the survey currently is not possible. Therefore, we identify two values that characterize the interaction with interviewers: the percentage of contacts that are transferred to an interviewer for the interview (the rest are robots and are irrelevant to the population survey) from the whole mass of numbers in the sample, and the percentage of completed interviews in the number of contacts transferred to the interviewers by the dialer robot.

As shown in Table 13, the percentage of contacts between potential respondents and interviewers in this survey was 6.0%, and the percentage of successful completed interviews among them was 9.3%. The average values of this indicator in 2022 were 7.3% and 7.7%, respectively. As we can see, the values of this measurement, even if significantly different from the average, are for the better. One can argue that the survey practice in the context of the special operation does not significantly worsen the quality of the sample so far. The shares of refusals and the population not covered by the survey, even if they do increase from time to time, return to the same level afterwards.

Estimating the Sampling Bias

Nevertheless, certain changes are taking place in the sample population that may affect the substantive findings of the surveys. Already this spring, we noted a significant decrease in the share of young people in the resulting sample. All this time we were implementing random sampling of cell phone numbers (RDD), which automatically reproduces the structure of the country's population that owns cell phones. As a result, we were supposed to get the age structure of the sample identical to the age structure of the Russian Federation population as per Rosstat data. This was the case throughout the entire period of representative telephone surveys in the Russian Federation.

Since March 2022, however, the share of young people has decreased. As seen in Table 2, on average in 12 surveys of the Russian population conducted from February to July, under different projects, but with the same sample (N=1600), the share of young people aged 18 to 29 was 14% (the table shows data on the part of surveys conducted in the Russian Federation). Then in the last two months the share of young people decreased by another 2 percentage points and now amounts to 12%. Since the paradata* of the surveys demonstrate the stability of respondent cooperation characteristics (the shares of refusals and successful interviews), we can assume that young people either physically exit the Russian Federation numbering space or use software applications and practices that allow them to avoid even fleeting personal communication with survey companies (use of auto-answer apps, the practice of not taking calls from unknown numbers, etc.).

Therefore, quantitative indicators in numerous surveys conducted in 2022 do not provide evidence of a decrease in the respondents' cooperation in telephone surveys. The refusal rate increases from time to time, then decreases, but no reason to claim that 2022 has significantly changed respondent cooperation has been found.

It is likely that we may also be dealing with a decrease in the percentage of men that are potential draftees who do not answer calls from unknown numbers, that is, the practice of drastically and deliberately limiting communication practices, including those over the phone, is spreading.

Changes in the General Population

For the first time in the post-Soviet history of public opinion research, events are dramatically changing the size and composition of the population, and this factor cannot help but affect public opinion research.

Changes in the sample population can be the result not only of a bias in data collection, but also of a deformation of the general population itself. There is ample evidence of the departure of large numbers of Russians from Russia after February 24. This is partly due to their political stance and unwillingness to fight, and partly due to the dramatic deterioration of passenger traffic to Europe and the United States, when people who prefer to move around the world a lot chose a place of residence more appropriate for such a lifestyle. Some of them have returned, but some of them have remained out of the reach of survey methods.

The mobilization decision announced on September 21 also led to an increase in cross-border mobility of Russians, primarily men between the ages of 18 and 50 subject to military service. According to various estimates, between 200,000 and 1,000,000 citizens left the country. According to Rosstat, as of January 1, 2022, there were approximately 23.4 million men between the ages of 18 and 40 residing in the Russian Federation.

In other words, between 0.7% and 3% of men left the country (taking into account that it was not only men who left). The extent of the reduction in group coverage in the sample remains too high, even if one accepts the most dramatic figures of cross-border migration of the country's population. It is likely that there is intra-border migration as well.

Another part of this stratum (men aged 18-50) are in the combat area, and although theoretically they could be covered by the survey, such coverage is unlikely to be significant. Various estimates range from 200,000 to 300,000 people involved in the operation, and this number will grow. This magnitude would also have little effect on the size of the general population. In other words, population deformation is undoubtedly occurring, but it is unlikely to be large enough to change the size of the population in any significant way. However, there is reason to believe that the structure of the population will change.

It should be reiterated that the loss of the youngest stratum in the sample amounted to about one quarter of it (from 16% to 12%), which in absolute numbers equals approximately 4.6 million. Even if we assume that the entire decrease in the young people in this group is men (which it is not), no departure, estimated at one million for all age groups and both genders, can explain such a decrease. Obviously, the washout of younger age groups from the sample can only partially be explained by a reduction in the general population.

*The term "paradata" is attributed to M. Couper. In the paper co-authored by Couper, Kreuter and Lyberg in 2010 it is defined as “automatic data collected about the survey data collection process captured during computer assisted data collection”.

[Couper M. P. (1998) A Measuring Survey Quality in a CASIC Environment. Proceedings of the Survey Research Methods Section, ASA. Achieving Quality in Surveys. Aug. Р. 41—49]

[Kreuter F., Couper M., Lyberg L. (2010) The Use of Paradata to Monitor and Manage Survey Data Collection. In: Proceedings of the Joint Statistical Meetings, American Statistical Association. Alexandria: American Statistical Association. Р. 282—296]

**A general population is a set of homogeneous units to which research results can be extrapolated. In this case, it is the adult population of Russia.

Comments